Hawaii <> Part One

In 1986, a vedic astrologer said to me, “Hawaii is the best place on the planet for you”. I was unimpressed. In the cult-like organization to which Elandra and I belonged at the time, Hawaii was considered the place to which organization members, who could not handle the intense discipline, would run away. They would spend their lives laying on the beach and smoking dope. That was not what I wanted to do with my life.

“Isn’t there anywhere else that’s good?” I asked. “Well, anywhere near the Pacific Ocean is good but Hawaii is far and away the best for you”.

I had been to Hawaii four times already and would return again briefly twice in 1988. Yet, in all of those times, I had never spent overnight there. I soon forgot about the whole incident. Interestingly, since 1968, other than a short and unhappy stint when I tried to return to London, I have never lived more than ten miles from the Pacific. It wasn’t until 1989 that a generous gift from a friend sent me back to Hawaii, this time for a week’s vacation.

The beautiful, mystical, magical Hawaiian Islands are alive with divine sound. Billowing waves breaking on white, golden, red and black sandy beaches, the trade winds softly rippling through the fronds of swaying coconut trees, hundreds of tropical birds singing their songs, the roar and hiss as molten lava meets the ocean currents. All of these make up the soundscape of an isolated and idyllic tropical paradise.

Over centuries, the native people of Hawaii created another soundscape, complementing the natural cacophony of their homeland. Like many other lands on this Earth, Hawaii is a land of the voice. Here the human voice is given huge respect. A common name to give a child, male or female is Kaleonani – Beautiful Voice. For a man or a woman to have an outstanding, even world class voice is considered to be normal and natural.

How did this come about? No one knows. Certainly the beautiful environment is an inspiration. But there are other places, Tahiti, for example; an equally beautiful island paradise, where people sing as naturally as breathing. Yet, in my admittedly biased opinion, the power and beauty of Hawaiian singing and chanting stand out above all others.

Hawaiian culture was held, until comparatively recently, by oral tradition. I have been told by those who know that there was, and still is, a written language in Hawaii. This is, of course, contrary to what the books and scholars will tell you. The knowledge of this script is being held kapu – in secret, until such time as those that hold it feel that the world is ready to receive its ike (wisdom).

Some hundred and fifty years ago, the missionaries established a way to write the Hawaiian language with the sole intent of spreading Christianity. As an unintended consequence of this action, all that is now known to the world of ancient Hawaiian tradition was then transmitted to Caucasians, who committed what they garnered to paper. Many of these Caucasians found within themselves a deep respect for Hawaiian culture and felt a responsibility to preserve as much as they were able.

As Hawaiian culture was systematically suppressed by missionaries and government, the old ones died along with their memories and their wisdom. It was, in effect, cultural genocide. Huge sections of cultural knowledge and tradition simply disappeared. Yet much still remains.

In spite of the proscriptions of the missionaries, and later the State Legislature which banned the Hawaiian language, both language and culture have survived. The culture has experienced resurgence in the last thirty years and is continuing to grow. The Hawaiian language, if not exactly flourishing, is being nurtured and kept alive by immersion schools and by those who stubbornly refuse to allow this most beautiful and mellifluous of languages to die.

To go deep into Hawaiian culture, you have to go deep into hula. Hula is the very soul of Hawaii. It is indeed tragic that so few people, even within Hawaii itself, have managed to go beyond the 1930’s movie image of hula, promulgated by Hollywood. The image of brown skinned women (hardly ever Hawaiian) in grass skirts (definitely not Hawaiian) swaying their hips to a song by Bing Crosby or Elvis still reigns throughout the world as the accepted depiction of hula, indeed of Hawaii itself. I was once part of a Hawaiian cultural show in Germany where a few people came and asked for their money back because there were no brown skinned women in grass skirts.

Hula involves the movement of the hips, both for men and for women. It is a sensual dance and, on occasion, blatantly sexual in a manner that is both ribald and hilarious. But the context is always that sex is a natural part of life and not any big deal.

Hula is about life because it is life. All aspects of Hawaiian life are reflected therein. Birth and death, farming and fishing, love and war, spiritual tradition, navigation by the stars, history and legend, all these and much more can be found in this ancient dance.

In hula, the dance and the voice are ineluctably linked. Even in its modern form, dancing hula to instrumental music without a singer is all but unthinkable. The dance is a vital adjunct to the story being told in the song. Dance and voice are inseparable, no matter how profound the lyric, no matter how trite.

In this day and age, modern hula (hula auwana) is associated with the guitar and particularly the ukulele, but always as instruments to accompany a singer. In ancient times, the old hula (hula kahiko) was danced to the voice; to a chant called mele. The voice was accompanied by either the pahu drum or a percussion instrument created from two gourds called the ipu heke. But these were only there to accentuate the rhythm by which the dancers kept time. The voice was that which gave the narrative and melody to the dance.

The other vital aspect of the Hawaiian voice in ancient times was oli. Oli means chant. This is an extract from an excellent article in Spirit of Aloha (Aloha Airlines magazine) called The Art of Oli by Joan Conrow.

A sound has largely disappeared from Hawai‘i’s valleys and forests, a sound other than the songs of now-extinct native birds. It’s the sound of the human voice raised in oli, in chant, speaking words thoughtfully chosen by the composer, carefully memorized and delivered by the orator.

Hawaiian culture was traditionally imbued with oli, as chants were a part of every aspect of daily life. Whether it was a fisherman offering a chant before setting out to fish or a kahuna, priest, chanting within the context of a sacred ritual, oli were ubiquitous. Indeed, even the Hawaiian creation story, the Kumulipo, is presented as a 2,102-line chant.

It was frequent, in pre-Western-contact Hawai‘i, to hear women chanting as they pounded tapa cloth or cleaned hala leaves alongside the ocean or a stream; to hear men chanting before planting taro in the fields; to hear families chanting to greet the dawn and the dusk, to acknowledge all the ancestors.

Chant was also used to pay homage to the recently dead. As Lili‘uokalani, Hawai‘i’s last queen, lay in state in 1917, according to S.M. Kamakau’s Ruling Chiefs of Hawai‘i: “… the body was viewed by a vast procession of people … the natives venting their sorrow in the oldtime oli or the uwe helu (lamentations.) … devoted attendants and loyal subjects [mourned] in song, chant recitations, oli or the weird, soul-piercing disconsolate wail of a grief-stricken heart.”

Chanting was a way of expressing gratitude, focusing intention, asking permission, acknowledging the gods, calling upon the forces of nature, seeking protection in short, oli were the utterances of a profoundly spiritual people who were deeply interactive with their environment.

Since they were human, with all the accompanying emotions, chant was used for more mundane purposes, too: professing feelings of love and admiration, asking for a favor or delivering a scolding, expressing praise or despair.

But with the arrival of the missionaries and new ways of doing things, oli began to rapidly subside from its once prominent role in daily life.

When I arrived for the first time (at least to stay overnight) in Hawaii, I had little idea of the great treasury of feeling and tradition in Hawaiian music and chant. It was not until my third visit that fate took a hand and gave me an unforgettable and life changing experience.

Returning from Maui to San Diego (where we were living at the time) required a stopover in Honolulu. A friend invited us to have dinner and then explore Waikiki. By some fluke (there are NO coincidences!) we arrived on the beach by the Royal Hawaiian Hotel just as the evening show was about to start. We were standing outside the Monarch Room, the hotel’s show room.

The Monarch Room has huge glass windows and doors. Normally the doors are normally open to the night, allowing air to circulate and passers-by to watch the whole show, free of charge.

As my wife and I stood there watching the house lights dim and the stage lights project their colors, there came a recording of some incredibly beautiful music with a thrilling narrative talking about the ancient gods of old Hawaii. I was enthralled. Then a large Hawaiian lady came out onstage. I didn’t know it at the time, of course, but this was Aunty Leina’ala Heine, a well known kumu hula (hula teacher). She began beating on a huge pahu drum and started to chant the first oli I ever heard.

The curtains opened to reveal a group of hula dancers, men and women, the men clad in malo, traditional loincloths. While Aunty Leina’ala chanted a mele, Auwa ’ia e kama, the dancers performed a hula kahiko, an ancient hula. I was intrigued as they moved their hips in wide circles for the traditional step known as ami.

From opposite sides of the stage, two small daises slid onto the stage and came together in the middle. On one dais, a man stood with a white double bass. On the other, a man sat cross legged with a twelve string guitar. They began to sing.

I had never heard anything like it. Their voices slipped easily in and out of harmony. At the same time, they soared into and beyond the highest level a man’s voice could be expected to go without breaking into falsetto. The music was rhythmic and exciting while still holding a certain spiritual quality.

I stood there with tears running down my cheeks, utterly captivated. This was the duo known as the Brothers Cazimero, at that time the top Hawaiian music act, and still riding high today. After three songs and to my intense frustration, our host called us away.

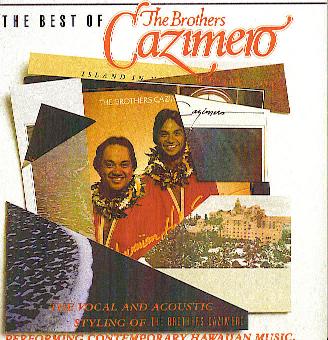

Our overnight flight deposited us in San Diego at around seven am. As soon as Tower Records opened that morning I was there. In their world music section, and somewhat to my surprise, I found The Best of The Brothers Cazimero, a selection of their most popular songs. Common knowledge says that CDs don’t wear out but, after playing it over and over for the next fifteen months, this one did. The songs on that CD spoke to parts of myself and my soul that I never even knew existed.

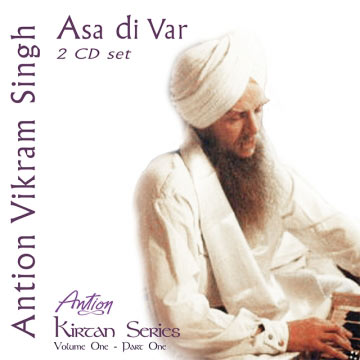

The most surprising aspect of this turn of events was that I had not felt like I needed a new musical discipline. I deeply loved Indian music and I especially loved Gurbani Kirtan, the sacred music of the Sikhs. I was not looking for more. It was as if the Universe said to me “OK, now learn this. This is what’s next for you”.

There was a recession in California in 1991/92 that brought my plumbing business to its knees. That, plus my love for the music and chant of Hawaii, precipitated our moving there in February of 1993. Our original intention was to settle on Maui but, after only a few days, I was directed to the Garden Island of Kauai.

Five months previously, Hurricane Iniki had devastated the island. Many houses had been destroyed, many people had left the island and the different communities on the island were in varying states of shock. Accommodation was hard to find. The saving grace was that, if you were in construction, there was plenty of work rebuilding the island.

It took us time to create a semi-permanent place to live. We lived in a tent for six months and, after that, in a yurt for five years. There was, however, never any shortage of work. Still, it took time to get my business re-established. All of this meant that I could not pursue my dreams of learning Hawaiian music and culture for which I now held an unslakeable thirst.

Hawaii <> Part Two

In normal times, there are plenty of cultural events on each of the main Hawaiian islands. They are the life blood of the community. But Kauai was in a state of shock. Thus it was some time before the cultural calendar there started filling up again. We made it a priority to attend any cultural event that was held and, as the number of events began to increase, we found ourselves out more and more.

The first Hawaiian concert we attended was in April of that year at Vidhina Stadium in Lihue. The community was still under enormous stress and, even seven months after the hurricane, destruction was evident everywhere. The concert offered welcome relief and a chance to have much needed fun.

During one of the performances, it was announced that there would be a special guest dancer. A tall, slim figure came to center stage. Clean shaven with soft features that were refined, yet unmistakably Polynesian, his graying hair was pulled back into a pony tail. His clothes were unique. They looked more like something from India than Hawaii with a long kurta-like shirt and slightly baggy pants, also made from soft material, that were gathered at the ankles. His long sleeves were rolled up revealing tattooed rings in Polynesian designs down the length of each forearm.

Even to my inexperienced eye, his style of dance seemed different and unique. His movements were graceful and deliberate yet sparing. His dance, telling the story of the beauty of the island of Kauai, was entrancing and easy to understand. He had a look of sheer ecstasy on his face. He was introduced as Frank Hewitt, although he now prefers to be known as Kawaikapu Hewitt. (His full Hawaiian name is Kawaikapuokalani – The Sacred Water of the Heavens).

As soon as he began to dance, I noticed that Elandra rushed to sit in front of the stage. I was impressed, but did not fell the need to move from my seat. Once again, I was getting my first sight of another musical virtuoso who would have a profound influence on my life, although I had no idea at the time.

In my hunger for Hawaiian music, I would try to listen to it on the radio as I drove to and from work (or anywhere else, for that matter). Incredibly, there was no regular Hawaiian music being programmed on Kauai. I was able to tune into a station from Honolulu but only on the parts of Kauai that were closest to O’ahu.

Nevertheless, began to find out more about the music and the artists. I found out that most of the songs that I found the most moving and entrancing, were written by the same man. His name: Kawaikapu Hewitt.

By 1996, things were close enough to normal that Elandra and I began to seriously consider finding ourselves a teacher. We had learned enough to know that everything cultural in Hawaii revolved around hula so the obvious thing to do would be to join a hula halau (dance troupe). Elandra wanted to be a dancer; I wanted to be a musician and chanter.

Every major island has a number of hula halau. As we familiarized ourselves with the way things happen in Hawaii, we found out that you cannot just walk into any hula halau and expect to be accepted. Things have eased somewhat over the last fifteen years but, in 1993, there were plenty of halau that would not accept white people. Even if you were able to get into a halau, there was often racism and cliquism within the halau. I also found out that hula is very political. This kumu (hula teacher), for example, would not associate with that kumu, if you had been with this halau you could not associate with that halau. Though after twenty years of Sikh politics, it all seemed pretty tame to me.

Still, we were invited to join a halau that accepted white people. After just a couple of weeks, I was castigated by one of the senior disciples (white) who accused me of flagrantly disregarding the traditions and protocol of the halau. I was deeply hurt since everything I had done had been under the direction of her husband who was also a senior member of the halau and Hawaiian to boot. I retired into myself and decided that I would just give up on the whole process.

A few weeks later, Elandra said, “There’s a new kumu who’s coming over from O’ahu every week to teach. He says that anyone can join his halau”.

“No”, I said, “I’ve had enough.”

“Well, I’m going even if you’re not”, she said.

When Elandra returned from the class she said to me, “Look, I talked to him. He says he’ll teach you to chant and how to accompany hula”.

“No”, I said.

“Well, at least come by and meet him”.

The next Thursday I showed up at the Outrigger Hotel at the end of class. The kumu’s name was Blaine Kia, a strikingly handsome Hawaiian with more than a touch of Chinese in his makeup. At the time, he was thirty one, exactly twenty years younger than me.

“Oh, yes,’ he said in what seemed to me to be rather too enthusiastic and jocular a tone, “I’ll teach you how to chant and how to play ipu heke”.

I looked into his eyes and I could see what he was thinking. “This funny looking haole (white) guy won’t last more than two weeks”.

I dutifully showed up for class the following Thursday. Blaine said “Hi” and went on to teach the class. I sat and watched. And observed. At the end of the class Blaine said “Goodnight”. This went on for six weeks.

And the end of that time, I suppose I must have convinced him I was serious, because he started to teach me.

Around that same time, he said to me “Bring your guitar next week, we’re going to do auwana (modern) hula”.

“OK”, I said “what are we going to do?”

“Kalihiwai, a song from my CD” he said.

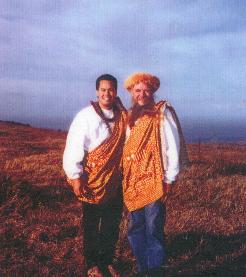

Antion and Blaine at Ka Hula Piko

I went home, got hold of the CD and thoroughly learned the first two verses of the song, knowing that he would not teach the dancers more than that during class. I memorized the Hawaiian words and the harmonies.

The next week at class, Blaine handed out the words to the song as he always did before teaching it. “Would you like a songsheet?” he asked me.

“No thanks”, I replied. He gave me a funny look.

In Hawaiian singing, the norm is for one person to sing a verse and then for everyone to join in for the second time through singing harmonies. That night, every time Blaine sang the verse for the second time, I joined in, word and harmony perfect. After that, he started treating me with much more respect.

Blaine was young for a kumu hula. His hula lineage was from a legendary teacher named Darryl Lupenui, who brought about a revolution in men’s hula in the early eighties but then died young. Blaine had also learned from the late Uncle John Ka’imikaua, about whom, more later. His other kumu was Kawaikapu Hewitt. This was great for me. I felt like a circle was being closed, bringing me back in touch with a man who had been such an inspiration to me.

Blaine had started teaching to propagate the lineage of ‘Ihi’ihilauakea (Darryl Lupenui). Over time, he began to introduce more and more of Kawaikapu Hewitt’s material, both songs and choreography, into his repertoire. I received a very thorough education in song, chant, cultural tradition and, even though I never danced, in hula itself. Even though I was mostly learning in the tradition of Kawaikapu, I began to feel the huge presence of ‘Ihi’ihilauakea. Which is why, even though I never met him, I always honor ‘Ihi’ihilauakea ‘o Kapuwailani ‘o Noenoe’ula as one of my Hawaiian teachers.

Blaine gave me the Hawaiian name of Pu’ukani o Ka Lani (the sweet voiced singer of the heavens).

Blaine stuck his neck out for me in many areas. He never said anything to me but I think he copped a lot of flack for giving such an unusual looking haole guy a prominent role in his halau. He was a dedicated and devoted man and I felt privileged to learn from him. It wasn’t long before I was playing guitar and singing with him for rehearsals and public performances of the halau.

My first public oli was at Ka Hula Piko on Molokai in 1998. Ka Hula Piko is an annual festival founded by the late Uncle John Ka’imikaua to celebrate the birthplace of hula according to Moloka’I legend.

Uncle John was an extraordinary man. Discouraged from learning about his Hawaiian heritage when he showed an interest as a young boy by his parents, he began to learn from his grandmothers. He was then taught by a 92-year-old woman named Kawahinekapuheleikapokane (Sacred Woman Traveling on the Night of Kane), who began mentoring him at age 14. The Molokai kupuna (elder) taught him 156 Molokai chants, ranging in length up to 928 lines – ‘an unbroken oral history of our people for 1,000 years,’ he once explained.”

His teacher assured him that his generation would fulfill the prophecy of a Moloka‘i chant from 1819, when Hawai‘i’s royal leaders ordered the destruction of the temples of the ancient Hawaiian religion and overturned the kapu system of rules that controlled Hawaiian culture. The Hawaiian people would be brought low to the earth, the prophecy warned, losing everything. But in time, there would be a resurgence of the culture. Uncle John felt that now is that time.. And Kawahinekapuheleikapokane told him that he and those who came after him would not have to live the kapu.

“All the knowledge I give you will be free of kapu,” she told him. “It will be taken at my time of death. There is no kapu, but there is a great kuleana (responsibility).”

Only after his teacher’s death when he was 16 years old did Uncle John understand that kuleana. In 1977, at age 19, he opened his own halau. “The night I opened it, I understood,” he said. “That first practice, I realized the kuleana: to educate and enlighten all people about our ancestral past.”

The event at the heart of the festival, takes place in the mountainous area known as Ka’ana, located on the heights of Mount Maunaloa, in the arid area of West Moloka’i. At around three am on Saturday morning, hula halau and committed spectators gather on the windy and often bitterly cold heights of Ka’ana. Sometimes there is a moon: sometimes not. Without a moon, there is no light to even see the dancers until the sky lightens in the East. That is not considered important. Each participant considers it an honor just to be there. The whole event is considered kapu (sacred).

Each halau is allowed one oli and one hula; there is to be no talking. The discipline is strong and strict, the respect palpable. It was in this pressure cooker that I performed my first public oli and I was very nervous.

As we sat back down on the dirt after our hula, I felt a huge whack on my back. I turned round and there was Blaine beaming at me.

“Good job” he whispered.

Later, at the day long ho’olaulea (festival) that follows, Uncle John was kind enough to congratulate me on my oli. That meant a lot to me.

I continued to practice with the halau and appear with them in public performance. Once, after a show at Kukui Grove Shopping Center on Kauai, an old Hawaiian lady came up to me after we had finished.

“I know who you are, I know who you are”, she called out to me.

“Who am I auntie?” I replied.

“You were Hawaiian in your last lifetime, but you were kolohe (naughty, bad), so you had to come back as a haole guy!”

In 1999, I asked Blaine if I could compete in the Chant division of the King Kamehameha Hula Competition. This annual festival features the leading oli competition in Hawaii. If the Merry Monarch Festival is the Olympics for hula, this is the Olympics for chanters.

“Yes”, he replied, “if you are prepared to work hard”. And so we began.

Blaine is extremely talented in many areas. One in which he particularly excels is this: if any of his students enters a solo competition such as solo hula, he studies their character and writes a song and a hula that is a unique reflection of their personality.

In my case, he wrote a chant for me in English that was translated into Hawaiian by his friend and fellow kumu, the very talented Michael Keala Ching. The resultant oli was about four minutes long, an eternity when you are out on the floor of a huge arena by yourself. It was called Ku Na Iwi. The oli told the story of someone (me) coming to Hawaii, of being entranced by the beauty, by the fragrances, by the traditions, but above all, seeking to know, to understand, to experience aloha.

We trained together for about two and a half months. Blaine gave selflessly of his time but the whole process was intense. We had a couple of knock down drag out arguments and he yelled at me a lot, but we got it done.

The night before I was due to perform, Elandra and I were in bed at my elder daughter’s house in the Tantalus district of Honolulu. I was so wired from nerves and excitement that I was half out of my body. I could feel the spirits moving in the jungle outside. All was silent in the house as my daughter was asleep.

Suddenly, I heard a deep rasping breathing, like something from a monster movie. Elandra heard it too. Then I remembered. I had seen Uncle John Ka’imikaua’s halau perform a Mo’o dance and make this sound by moving their hands in front of their mouths while inhaling and exhaling loudly. Mo’o are the legendary giant lizards that populated ancient Hawaii and are said to still exist although rarely in their physical bodies. According to tradition, this was the sound they made.

We felt a huge presence enter the room. It was neither good nor bad. It was simply curious. It wanted to know who or what was impinging on a space where it lived that was normally beyond the reach of humans. The presence examined us and then left. As it left we heard the breathing again.

I was due to go on at around 4pm. I spent the whole day in the halau dressing room (they were competing in the hula competition) practicing. I was more nervous than I have ever been in my life.

Finally, it was time for me to chant. At these competitions there is always a hubbub of conversation when one act finishes which only subsides when the next begins. My name was called and I strolled into the middle of the Blaisdell Arena, a huge basketball venue. By the time I reached my place on the floor, you could have heard a pin drop.

The oli went well and the crowd cheered me as I left the floor. As I stood, dazed, out in back of the arena, a young Hawaiian woman rushed up to me and hugged me. “That was WONDERFUL!” she said breathlessly. When they announced the competition results, I recognized her as she accepted the prize for best chanter.

After the competition ended, Blaine gathered all of the leis from all of us in the halau and took them to the grave of ‘Ihi’ihilauakea, to lay them there in tribute.

I didn’t win anything but I felt I achieved a great deal by even competing.

Around 2000, an informal group of ladies who wanted to practice hula formed on Kauai. Many of them were students of the well known writer Serge King and his organization, Aloha Internaitonal. Under the direction and inspiration of Kawaikapu Hewitt, they later were given the title of Halau Na Lei Kupua o Kauai and their director, Susan Pa’inui Floyd was given the title of Kumu Hula. It is very unusual and a great honor for a Caucasian to be so named.

While I was never a formal member of this halau, I had the privilege to accompany them musically for many of their performances. In return, they would often come to dance at my shows on Kauai and on O’ahu. I owe a great deal to them.

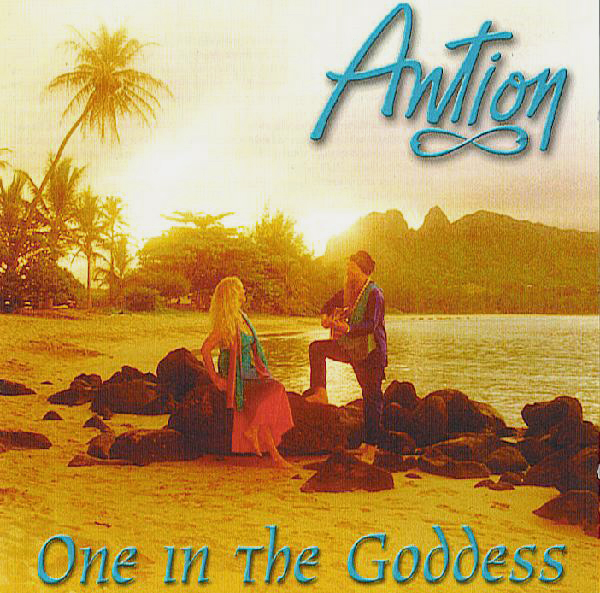

In 2001, I began to record my first CD, One in the Goddess. In looking to forge a link between my Indian and Hawaiian cultural heritages, I found that they had a strong Goddess energy tradition in each culture.

For the Hawaiian part, I drew heavily upon the compositions of Kawaikapu Hewitt, some of which had been co-written with Blaine.

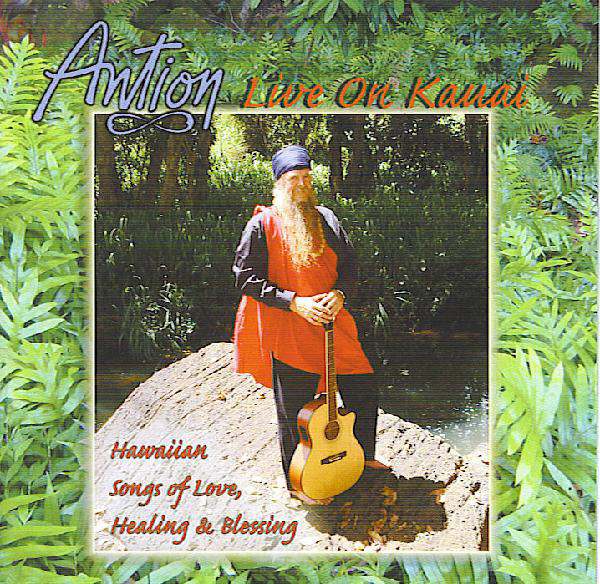

My second CD, Antion, Live on Kauai, could not have been made without the help and magnificent songs of Kawaikapu Hewitt.

I fell compelled to honor both these men for the powerful traditions and teachings that they selflessly shared with me.

I must also honor the late Uncle John Ka’imikaua for his constant inspiration and encouragement, as well as the late Darryl ‘Ihi’ihilauakea Lupenui for inspiration from beyond.

Antion's Albums