From Rock Star to Ragi

If I really wanted to name drop, I would tell you that it was all Eric Clapton’s fault. OK, that’s stretching it a lot … but it was Eric who got me started into Indian Classical music.

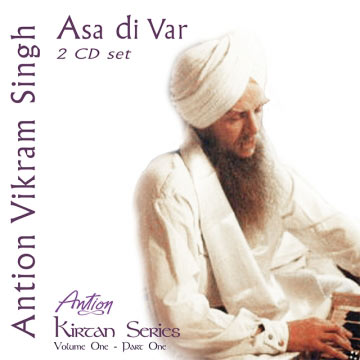

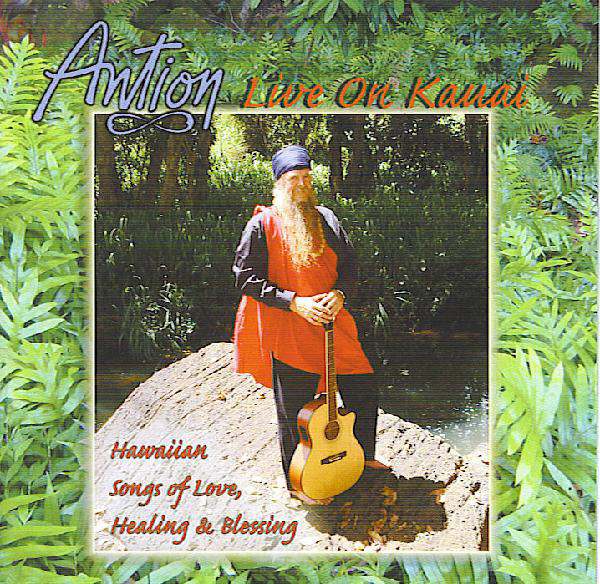

Antion has had an amazing life, with many musical, lifestyle and geographical transitions. One of his most powerful transitions was from a 60s rock star to a singer of Sikh sacred music, a Ragi.

In this series of articles, he describes his journey, with a strong focus on the music.

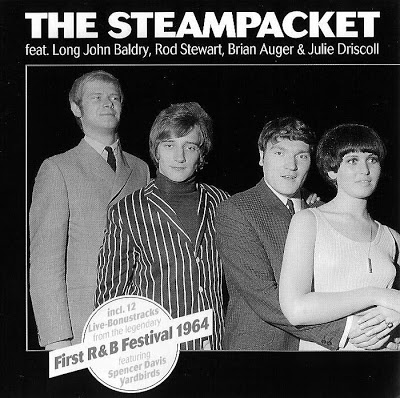

In August of 1965, I left Dusty Springfield’s backup band, The Echoes, and joined Steampacket. More accurately I joined Brian Auger and The Trinity who were part of Steampacket. Steampacket consisted of:

- Brian Auger and the Trinity

- as back up band, for the singers:

- Long John Baldry

- Julie Driscoll

- Rod Stewart

What a bunch of characters! Long John was 6ft 7 inches tall, slim, pompous, always elegant and extremely gay in an age when it was not fashionable to be out of the closet.

Julie was young, only 18 but with the face of a model and an iron determination to succeed. She was sensitive and easily hurt but covered her sensitivity with a fiery temper.

Rod? Well, Rod wasn’t much different than his image of today. He was just getting away from being known as Rod the Mod but his hairstyle and cloths were about the same then (bright and outrageous) as they are now.  Brian Auger was best described as relentless. His keyboard playing was intense, his energy enormous and his sense of humor (mostly lifted from the Goon Show) inexhaustible, except when he was overtired or angry, which was not often.

Brian Auger was best described as relentless. His keyboard playing was intense, his energy enormous and his sense of humor (mostly lifted from the Goon Show) inexhaustible, except when he was overtired or angry, which was not often.

The other musicians in the Trinity were: Ricky Brown, a brilliant but moody bass player with a dry sense of humor and Mickey Waller on drums. Mickey was hard to describe; you could even say he defied description. A fantastic drummer, offstage he lived in his own reality. if he wasn’t studying some obscure foreign language, he was figuring out ways to invest the £1000 he had managed to save (very few musicians in those days had savings accounts). Or else, being an incorrigible hypochondriac, he would be trying to decide which latest, exotic disease he had contracted.

In the burgeoning R&B scene in mid 60s England, we were always coming into contact with other musicians, many of whom later became household names. One of these was Eric Clapton. I would often run into Eric at the after hours or “in” clubs that we musicians used to frequent, especially at the Cromwellian on Cromwell Road in Kensington. Initially, our acquaintanceship was polite but distant.

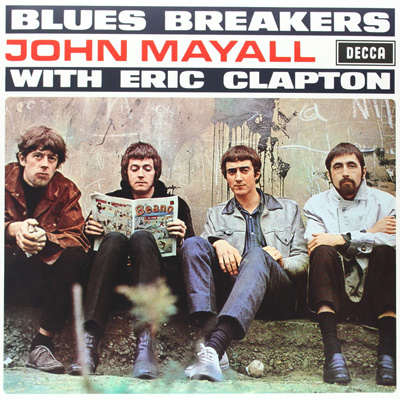

One Saturday night in April of 1966, Steam Packet played a double bill with John Mayall and the Blues Breakers, somewhere in East London. It was one of those nights when everything goes just right and the crowd is wonderfully appreciative. For the final number, John and the Blues Breakers joined us on stage. I don’t remember the song, but I do remember that it was an up-tempo blues.

In those days, Eric, while a fine blues player, didn’t have the extensive technique he has since developed. Even though the crowd was chanting “Clapton, Clapton”, like a bunch of Brit soccer supporters, Eric was struggling through the song, not able to play convincingly at that fast tempo. I, meanwhile, with my jazz approach, was playing the crap out of the thing. I could tell Eric was uncomfortable.  A couple of days later, in the Cromwellian, Eric walked up to me and said “Oh man, you really blew me off the stage the other night” and walked away. After that, he became friendlier to me, eventually inviting me over to his flat one day in May of that year.

A couple of days later, in the Cromwellian, Eric walked up to me and said “Oh man, you really blew me off the stage the other night” and walked away. After that, he became friendlier to me, eventually inviting me over to his flat one day in May of that year.

He had left John Mayall and his new band, Cream, was in its formative stages. Eric showed me some art work he had done on a logo for the band. Not knowing that he had been an art student, I was surprised at his artistic ability.

Around that time, George Harrison’s interest in Indian music and the sitar was getting a lot of publicity. He had just begun his student/teacher relationship with Ravi Shankar. The Stones had recorded Paint It Black with Brian Jones on sitar. Consequently there was a buzz in the Brit music press about Indian music and its impact on British Pop.

For no particular reason, other than I knew Eric to be very hip and always aware of the latest thing, I asked him what he knew about Indian music. By way of an answer, he walked over to his rack of LPs and pulled out a couple of albums. “These are a couple of records I bought at the Indian import shop on Oxford Street”, he said. “If you’d like to, why don’t you take them home and have a listen”. I don’t know if that could be defined as a life changing moment. Certainly, I didn’t feel any different. But I will never forget the effect those records had on me.

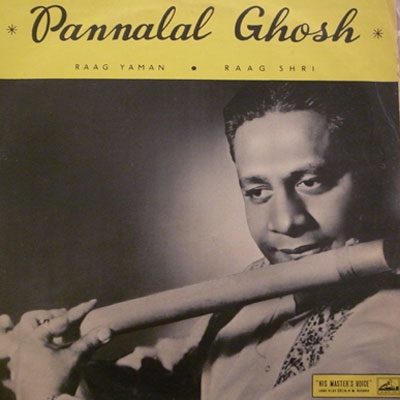

One disc, a recording of a classical bamboo flute by the late Pannalal Ghosh, was the most etheric, dreamy thing I had ever heard. Listening to it, I was both enchanted and mesmerized. The other disc was made of sterner stuff. There is a style of Indian Classical Singing known as Dhrupad. It is slow, regal and majestic. Popular several hundred years ago, Dhrupad has since fallen out of favor. Yet it holds a place as an integral part of Classical Indian music. For many years, the tradition of Dhrupad was upheld by a family known as the Dagar Brothers.

The second album that Eric lent me was one of their recordings. I returned the LPs to Eric within a week or so. I had gone to the same Indian import shop to buy my own copies. Somewhere, in my archives, I still have the Dagar Brothers’ recording. Later that year, I bought another LP that would expand my horizons even more. The recording was of Ravi Shankar, master of the sitar, and his brother-in-law, Ali Akbar Khan, master of an instrument called the sarod.

The recording was a “jugalbandi” or duet. In spite of my interest in jazz and all of the exceptional musicians to whom I had listened and whose work I had studied, I had never heard such instrumental mastery nor such an empathetic exchange of musical ideas. I was hooked. I also found that the sound of the sarod, a deep vibrant ringing sound, appealed to me so much more than the thin buzzing of the sitar.

The beginning of 1967, found me preparing to leave for the US with The Animals for my first tour there. We arrived in New York at the beginning of February, 1967.

In the latter part of the US tour, we found ourselves in California. Upon my arrival, one of the first things I did, was to buy more albums of Indian music. In the US, the Indian music craze was taking off and US record companies were signing outstanding Indian musicians.

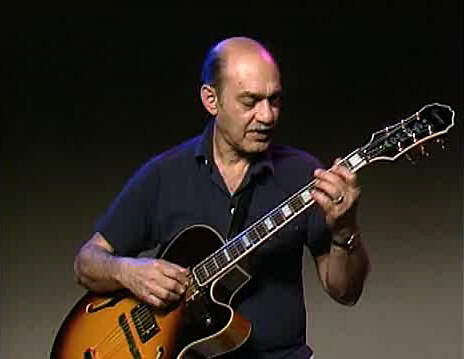

Richard Bock was a jazz record producer in L.A who started the label Pacific Jazz. It specialized in what was called West Coast jazz at a time when almost all jazz records were produced in New York. I already had some of the albums that Dick had produced in my collection in London, particularly by Joe Pass.

As his own interest in Eastern spirituality and Indian music grew, Dick had approached Ravi Shankar and asked Raviji to sign with his label. Raviji told Dick that he would not record for a label that had “Jazz” in its title and so Dick began “World Pacific Records” This was, perhaps, the first World Music label.

(Note: Having spent forty years immersed in Indian culture I use “ji”, an honorific suffix that used everywhere in India, from force of habit. At the time I certainly would not have called him Raviji. To be polite, I would probably have addressed him as “Punditji” as his official title is Pundit Ravi Shankar.)

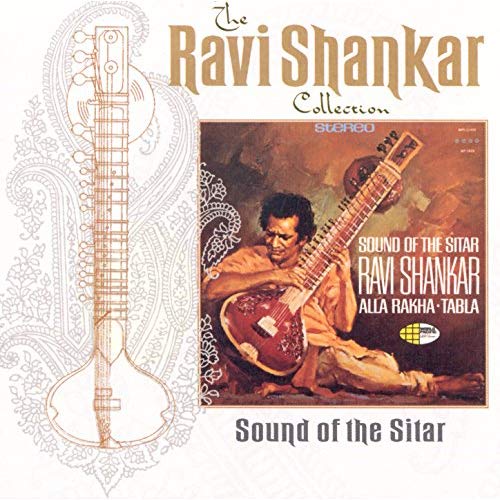

I bought two of the albums that Dick had produced: The Sound of the Sitar with Raviji and The Sound of the Sarod with Ali Akbar Khan. In London you could only buy Indian music albums that had been imported from India. In those days, and for many years after, most things manufactured in India were of poor quality, books especially. The covers of Indian LPs were poorly designed and tended to quickly fall to pieces. The US albums I had purchased were well designed and made from top quality materials. The sound quality was excellent, a huge step up from the thin sound of the Indian recordings.

Although I knew more about Ravi Shankar, it was the music of Ali Akbar Khan that captured my imagination. The Sarod, which was Khansahib’s instrument, has no frets. The fingerboard is made of stainless steel. The left hand presses the strings rather like a violin, except that the player uses his nails as well as his fingertips to hold the string against the fingerboard. This gives the instrument a fuller, darker sound compared to the somewhat buzzy sound of the sitar. The sarod is plucked with a pick made of coconut shell.

But it wasn’t just the instrument. There was something about the player. In later years I came to know Khansahib, as Ali Akbar Khan is known to all. He is an immensely complex man with many sides. As I listened to this album, it became obvious to me that here was one of the most emotionally expressive musicians in the world. In particular, his ability to express karuna (spiritual longing) was off the scale as far as I was concerned. I was deeply intrigued.

The jazz albums that I had bought in New York began to spend more time in my suitcase and less on the portable record player we had carried with us from the East Coast.

Yet jazz was still my first love. When I had arrived in New York, the first thing I had done was to visit as many jazz clubs as I could. I was still knocked out from having run into my guitar hero, Joe Pass, at a TV studio in LA. If someone told me that I was about to eschew jazz for another musical form, I would have laughed in their face.

At the end of the US tour, in the middle of April, 1967, we flew to New Zealand to begin another tour which would also take us to Australia.

Eric had been urging me to try LSD. He said that it would broaden my perceptions and allow me to see life in a totally different way. I decided that I would and we agreed to take it in Auckland on our day off.

The day before we arrived at our hotel in a town called Rotorua, about one hundred and twenty miles South of Auckland. Rotorua is a very unusual place as the whole town is built over a thermal area. No one in town needs a hot water heater; water comes out of the ground hot. Every hotel there has at least one hot mineral pool.

Our hotel was called the Geyserland Hotel. All of our rooms had balconies that overlooked a state park with the Maori name of “Whakarewarewa”. From each one of our balconies we could look out over boiling mud pots, surging geysers, steam belching out of the ground and other remarkable sights. Eric suggested that this was too good an opportunity to pass up. I didn’t quite understand why he said that, but we agreed to take the LSD that night, after the gig, and we did.

As you might well imagine, there were many adventures that night, but let us leave those stories for another time. What follows is what I would like you to know about that night.

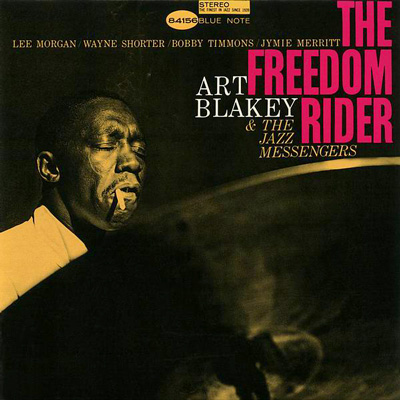

Someone said, “Let’s put some music on.” I had accumulated quite a collection of albums crossing the States, many of which were jazz. I pulled out Freedom Rider by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers and put it on. Within a few seconds I realized that this was not what I wanted to hear. I could feel the accumulated anger from hundreds of years of slavery welling up in this music. Every drumbeat felt like someone was kneeing me in my groin. I quickly pulled out Ravi Shankar’s The Sound of the Sitar and put it on. The music seemed just right, a constant flow of spiritual energy. That was the end of my love affair with jazz. Eventually, I sold all my jazz albums.

I transferred many of my Indian music albums to cassette and would take them on the road with me, playing them on what was one of the first stereo cassette players manufactured. I had bought it in New York at the start of the tour and it was my constant companion on the road. When we were in hotels on tour, we would congregate after the gig in our road manager’s hotel room. I would wait until everybody was royally wasted and flat on a bed or on the floor (a frequent occurrence!!) and then slip on an Indian music cassette. The more I listened, the more my appreciation grew, the more Indian music became part of my soul.

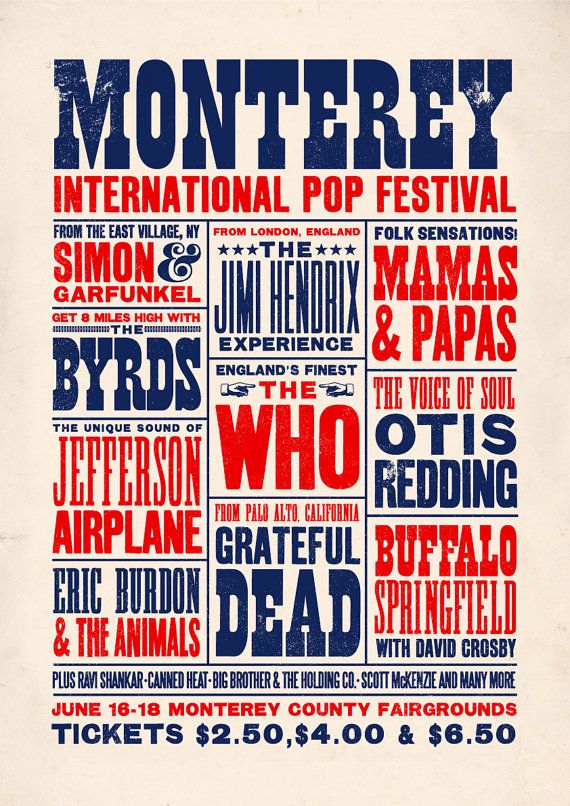

When we returned to London, it was May and the “Summer of Love” was in full swing. Within a few weeks, Eric Burdon heard that the Monterey Pop Festival was taking place in the middle of June. He demanded that his manager move hell and high water to get us on the bill. Less than six weeks after arriving back in London, we were on our way back to California as a last minute addition to the festival.I knew that the Monterey Fairgrounds was the home of the Monterey Jazz Festival. We had only just played there in April and it had been wonderfully inspiring to play on the same stage where so many jazz greats had performed. I was literally ecstatic about returning to the West Coast.

One of the highlights of the festival weekend was Ravi Shankar’s concert on the Sunday afternoon. About an hour before the performance, I made my way into the enclosure in front of the stage with prime seating reserved for festival performers. Since I was the first person in the arena, I made sure I got the best seat in the house, then sat and watched as the seats around me filled up.

The weather was grey and miserable with the hint of a light drizzle falling. Typical Monterey Peninsula summer weather! The same conditions prevailed for most of the weekend.

The Fairgrounds were situated in the flight path of the Monterey Airport. Every ten minutes or so, a light plane or passenger jet took off with a roar that blotted out most of the sound from the stage. The cloud cover was so low that the offending monsters were all but invisible; occasionally a dark shape could be glimpsed through the clouds.

Finally, Raviji took the stage, accompanied by Alla Rakha, his long time musical cohort on Tabla. As someone who has done plenty of awful gigs, I know well the look on the face of an artist who does not want to be at a place where he has committed to perform. Raviji had that look.

He sat down on a carpet covered dais in the middle of the stage and began to tune his Sitar. Incense was burning on the stage and a small electric heater had been placed near the musicians. It was not warm. Every time a plane roared across the sky, Raviji looked up with utter contempt on his face, and then resumed tuning. I happened to glance at my watch when he came on stage, then again when he was ready to play. He tuned his sitar for a full half hour. It seemed to me that he was procrastinating. He was not acting like a man who was ready or even wanted, to play.

Then magic happened. As he reluctantly finished tuning and put down his sitar, the crowd stood as one and gave him an ovation. The energy shifted. Raviji gave the first hint of a smile and said “If you liked the tuning so much, perhaps you will enjoy the music”.

As is customary in Indian Classical concerts, he began with a formal interpretation of an appropriate raag. In this case it was Raag Bhimpalasi, a powerful raag, suited to the afternoon. As he played the alaap, the long melodic introduction, you could see him beginning to relax. He would still glare at the sky as an occasional plane impinged upon the music.

One raag followed another and the rapport between audience and performers grew deeper by the moment. Finally, during a Sawaab-Jawaal (musical question and answer) exchange between Raviji and Alla Rakha, a plane flew overhead. This time, instead of glaring, the two of them were having so much fun that they both just shrugged their shoulders, laughed and carried on with the music.

The final composition, a Dhun, done in the traditional Thumri style, built to a climax so intense as to be almost unbearable. Near the crescendo, a stoned hippy ran out of the crowd and began to forward roll his way up the aisle toward the stage. Regrettably one of Pennebaker’s film crew immediately ran over and immortalized this attention-seeking act on film. I found myself wishing that the cameraman had ignored this boorish distraction from Raviji’s sacred music.

A few minutes later the performance finished and the crowd rose to their feet. There were standing ovations, flowers and tears. And a wonderful feeling that, just maybe, the world could be healed through music.

As Eric wrote in our 1967 single Monterey “Oh, Ravi Shankar’s music made me cry” I believe that there were few in the audience who were not deeply moved by Raviji’s performance. I know I was.

It was the first performance of Indian Classical music that I had seen and it left an impression on me that would stay with me for the rest of my life. I desperately wanted to be a part of this music and make it a part of me, but I didn’t see how it could be possible

The next morning we arrived at the Monterey Airport to catch a flight back to LA. There, also waiting, were Raviji and Alla Rahka. At that point in my young life, I had been around so many of the top names in the music business, that I was not easily impressed. But, seeing Ravi Shankar up close, I was quite star struck and felt more than a little nervous. I approached Raviji and told him how much I enjoyed the show. After he thanked me, I found myself at a loss for words. He graciously continued the conversation by asking me where I was from and we made polite conversation for a few minutes.

In December of that year, back in London after a fall tour of the US, I saw that Ali Akbar Khan was giving a concert at the Royal Festival Hall, the major concert venue for Western classical music in London. I took as much LSD as I dared while sill being able to hold it together to drive (which was a very small amount indeed!) and drove my yellow VW bug through a cold, rainy, miserable, Winter night in London to the South Bank of the River Thames, where the Festival Hall is located.

After finding my seat, I sat, wondering what the performance would be like. This was only the second Indian music concert I had attended and I was still not quite sure what to expect. I did realize that it could not possibly invoke the kind of excitement that Raviji’s performance at Monterey had.

There, during an epoch making weekend, in a California location full of excitement and musical revolution, Raviji had everything going for him except the weather and his own apprehension. His music, plus an incredibly receptive crowd, had created an event that is still being talked about more than forty years later.

For my first experience of Khansahib’s music in concert, I was looking at a medium size crowd manifesting a pleasant but hushed ambiance in a smallish recital room on a cold, rainy December night in London. I could not but wonder if my experience would be anticlimactic.

I need not have worried. The power and artistry of Khansahib’s music was such that I was transformed from his first note. As the concert progressed, I found myself drawn in to his virtuosity and the depth of his musical expression. I sat mesmerized for its two and a half hour duration.

The last raag, Misra Mand, one of Khansahib’s favorites, took me to a level of ecstasy I had never previously touched. In his rendition of that raag, I found perfection of form, clarity of expression and powerful, uplifting melodic improvisations. Above all, I found a musical manifestation of spiritual energy such as I had never before experienced, even in a dream.

I don’t know if that performance was anything special for Khansahib. For him it was probably just another night on tour, another gig, maybe one of the better ones. For me, it was way beyond anything I had ever heard.

Unlike Raviji’s well-documented performance at Monterey, which resulted in several album releases and a movie, I don’t believe anyone recorded Khanshib’s performance. The hall was reasonably full but not crowded; the audience response was enthusiastic, yet measured. There was no sense of history being made. However, my history changed that night.

More than forty years later, Khanshib’s music and the effect it had upon me on that cold, December evening, is still emblazoned on my soul. Certainly, I was under the influence. But it was the music that affected me so deeply, not the acid.

I had been listening to music for years, often under the influence of drugs. In so doing, I had often been moved, sometimes to tears. Yet what I heard, that night, was different. It was music at a much higher level; music was that was more spiritually connected than any I had known before.

The power of that night’s performance showed me that music could be much more of a tool for raising consciousness than I had previously imagined. In realizing that, my life changed. I knew that Indian music was in my future; I just did not know how.

Copyright 2014

Antion's Albums