After we played our first set, it was time for Jimi to do his thing. Chas introduced him and he took the stage with Brian, Roger Sutton on bass and Clive Thacker on drums.

And James Marshall Hendrix playing for the first time on a James Marshall amp, a pleasant association that would endure for the rest of Jimi’s short life.

For sure he played Hey Joe, as I already said, I remember the other songs – maybe three more – as all being blues based. They would have had to have been, just because of the short time of rehearsal.

Naturally I was interested and I watched him carefully. Jimi was going all out. He played his guitar behind his head and played with his teeth (although I still maintain he was doing hammer-ons and pull-offs while appearing to use his mouth).

The crowd loved him. He made a huge impression that night. It was from that one night that the legend of Hendrix was born. The following June, the Hendrix legend would be born again, this time in the USA, at the Monterey Pop Festival.

One of those Jimi impressed was top French singer Johnny Halliday, who would ask Jimi to join him on a tour of France that would start in a few days. Thus the Jimi Hendrix Experience would take shape – very, very quickly. More on that soon.

I took my place back on stage – not feeling the least bit threatened, I hasten to add – and finished the set with Brian.

Afterwards Jimi came up and told me how much he enjoyed my playing. Later, in two separate interviews, he would name me as one of his favorite guitar players along with Clapton and Beck.

In December of 2014, I was browsing in the Kapa’a Public Library (that’s in Hawaii, folks) when I came upon Sharon Lawrence’s book – “Jimi Hendrix: The Man, the Magic, the Truth” – which I never knew existed.

In the book Sharon quotes Jimi talking about that night when he sat in with Brian Auger and describes me as a “really helpful and friendly cat”.

He also talks about a dream of his to create a center where his musician friends could come to jam and exchange musical ideas. When asked who he would invite he cites Clapton and Beck. Then he says “and Vic Briggs – I learned from him!”

How strange that it took me precisely 48 years to find out that Jimi had such a high opinion of me.

I walked out of the Scotch that night not realizing that rock music was about to change radically. Nor that Jimi’s presence would have an indirect effect that would radically change my life.

Elandra asked me this morning why I thought Jimi was so successful – apart from the obvious – his enormous talent and originality.

One reason is that the music scene in London was so ripe, so ready for new directions. The beginnings of the psychedelic revolution were in place but they were way underground and facing hostility and suspicion even from the established music press of the time.

Jimi brought a sense of outrageousness and a desire to break down walls – racial, cultural and musical. Of course he wasn’t the only one but he blazed a trail for many other Brit musicians to get over their Englishman’s reserve and be outrageous.

The first Rock band to hit it really big in the UK was The Shadows, which was in the late 50s. For those Americans who have never heard of them, they were in a similar vein to The Ventures – essentially a guitar instrumental group, playing surf music before it was known as such.

The Shadows were good musicians but they were showmen. They wore sharkskin suits and did dance routines while they played their instrumentals. They were entertainers, first and foremost and really quite conservative.

When the British Blues movement started in earnest, say 1962-63, most of the Brit Blues players had a strong purist streak in them. They felt that the Blues was serious music and did not want to be thought of as showmen. So they did not move on stage.

Clapton, Peter Green, none of them moved.

If you see live videos of the Beatles, they never moved, other than shaking their upper bodies and heads. they just stood there and played their music. Even Jagger in the early days of the Stones would just stand there and sing.

There was also the question of Brit reserve and stiff upper lip, as well as perhaps some inhibitions along the lines of “White Men can’t dance!”

Jimi had no such limitations. His lithe movements and the projection of his own musical and sexual energy came so naturally to him. He had played the Chitlin’ Circuit and knew that you had to be a showman to get and hold peoples’ attention.

Jimi did not fit in in New York. He was too white for Harlem and too black for the Village. Perhaps he didn’t initially fit in in London but London soon changed to accommodate him.

To be honest, I didn’t really grok what had happened that night. To me it was just another gig – albeit with an interesting interlude. And yet I was amazed how much it stuck in my memory.

The events of that night were so clear in my mind that, when I actually started looking at books about Jimi – maybe in the early 90s – I was flabbergasted to see that Chas Chandler had told everyone that this event happened at Blaise’s. To this day, Brian Auger swears it was The Cromwellian. Although when Brian talks about the picture in his mind of that night, he describes The Scotch – not the Cromwellian.

In only three weeks I would run into Jimi again, this time in a foreign country. And, on that occasion, it would be my turn to have my life expanded beyond my wildest dreams.

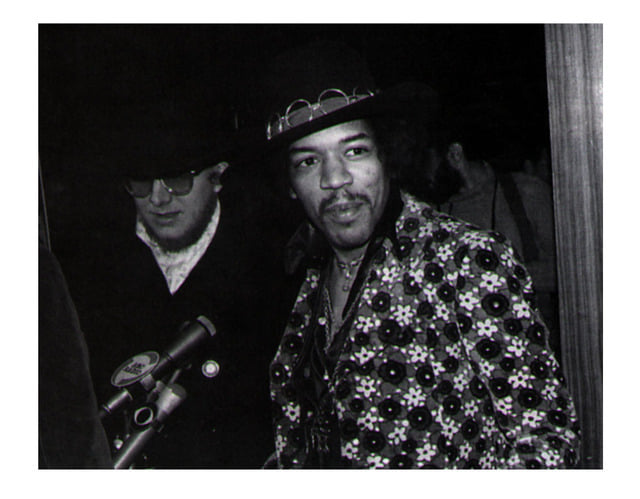

The Pic is me and Jimi in New York, January 1968.

Recent Comments