24th July, 1967

I returned to London with a swagger in my step. After all, I was 22 years old and I had played not only the first rock music festival in history, but also two legendary venues in California. I would like to think I was not full of myself, but I probably was, even if I tried not to be.

Although the San Fran musicians I met were mostly easy-going guys, they had a very low tolerance for attitude. That was not the way to get yourself noticed over there. I took note and certainly tried to bring a laid-back California attitude back to London, although I’m sure my enthusiasm for things West Coast probably riled some people.

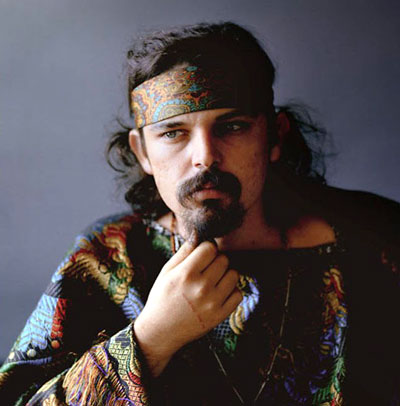

I had acquired Grateful Dead and Pigpen tee shirts (Pigpen was the organ player with the Dead at that time, see pic). I wore these on alternate days as badges of honour. Rest assured, people noticed.

I had acquired Grateful Dead and Pigpen tee shirts (Pigpen was the organ player with the Dead at that time, see pic). I wore these on alternate days as badges of honour. Rest assured, people noticed.

Our return to London marked a fundamental shift in my consciousness. I now wanted more than anything else to go live in California, yet I could not envision it happening.

We were still a British band and our base was in London. We all had commitments there, plus that’s where our management was located. It seemed impossible that we could just pull up and head to the West Coast.

I knew some of the others in the band were feeling the same pull to California. While Barrie Jenkins and Danny McCulloch chose to spend the rest of their lives in the UK, John Weider, Eric Burdon and I chose California. I lived there for 25 years before moving to Hawaii and then New Zealand; John and Eric still live there.

Eric, generally being the spokesman for the band, began to talk more and more in interviews about the California scene, while I had an interview in one of the Brit music tabloids, entitled Vic Briggs of The Animals and the American Dream.

All this Americanophilia did not sit well with the Animals’ British fans and the Brit music press. But we couldn’t help it. We were just so enthused with what was going on over there and the way our music was understood and appreciated.

Moving between San Francisco and London, I was able to study the differences between the California Summer of Love and the Brit version.

American hippies were a lot more serious about their intentions, perhaps because of the Vietnam War, the protesting of which was an integral part of their movement. When you have the likelihood of being sent to fight and die in a third world hellhole, it gives you focus and passion about your cause.

The Brit hippies were not under the same kind of pressure. Sure, there were political issues and generational conflicts, but war was not one of them.

The Brit hippies were not under the same kind of pressure. Sure, there were political issues and generational conflicts, but war was not one of them.

While we were in California, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had been sentenced to three months and one year in prison respectively for drug offences. Their sentences were quashed soon after we arrived back, mainly because of an editorial in the London Times. Other less celebrated individuals were not so lucky.

It was obvious that the Metropolitan Police had been given orders to put pressure on and harass anyone who looked like they might be using drugs. There were constant reports of young people, mostly in hippy style clothes being hassled by the law.

There had been an underground subculture in London for some time and these guys could be quite serious about their aims and goals, rather like the Americans. But, as the summer progressed, psychedelia, hippiedom, call it what you will, became a pop culture craze, egged on by the inevitable Brit tabloid press, being encouraging and condescending at the same time.

I found little substance to the hippy movement in the UK. It was disappointing.

The Brit hippies and the Americans each drew upon their cultural traditions and legends. These were markedly different. The Americans went for Cowboys and Indians. The Brits for Castles, Knights, Fairies and Elves, sometimes even veering into children’s fantasy stories like Wind in the Willows.

In California, you would see cowboy hats, lots of denim and Native-American style fringed buckskins. In London, flowery paisley shirts and dresses, velvet jackets and pants, almost an Edwardian look.

American hippy music was based in the blues and often had strong political leanings.

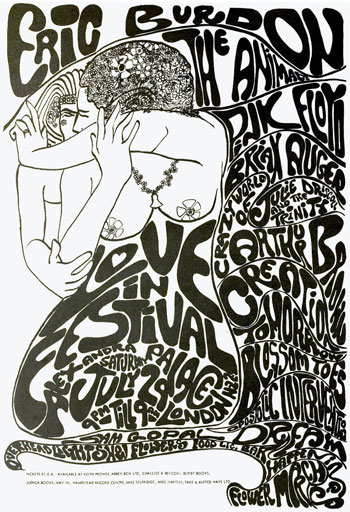

Brit psychedelic music, while strongly embracing blues, often mixed in wistful, almost classical themes. A good example would be the music of Pink Floyd at the time of Syd Barrett (see pic of Pink Floyd at Alexandra palace). His lyrics spoke of times of fantasy, castles, knights, ladies and even children’s classics.

Although few of us remembered the war, its shadow was with us in our early formative years. Perhaps Brit psychedelia was looking to a golden age of childhood and innocence, a way of channeling uniquely British traditions into a different and often scary age.

For me, British hippiedom was more of a fad and a fashion statement than a deeply-rooted cultural revolution. Which is not to say that the Brits did not have a profound effect worldwide, they did. It was mostly through their music though, especially that of The Beatles.

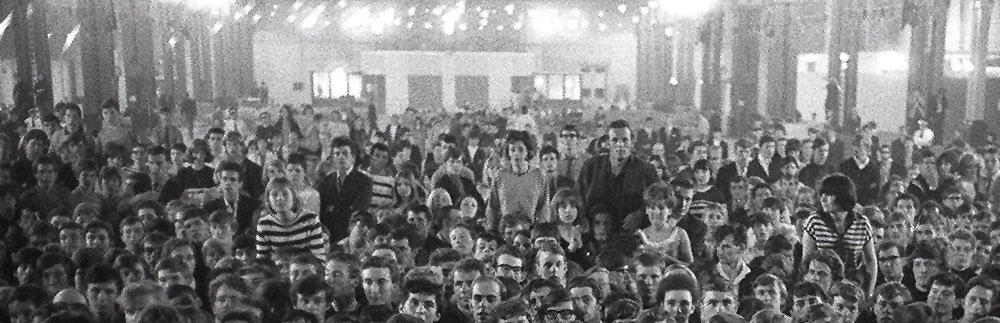

Very soon after arriving back, Saturday July 29th, we were due to play the “Love In” at the enormous Alexandra Palace exhibition center (see pic). This seemed to be an effort by regular promoters to capitalize on the hippy craze by recreating the 14 Hour Technicolour Dream that had been so successful at the same venue back in April. The first event had some idealism behind it; this one did not.

Nevertheless, a lot of hippy types showed up and created a mystical atmosphere. The event appeared to be a commercial success.

Our set was well received. We played all the usual songs plus the Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit. I had my Indian sitar, to which I attached a contact mike, and I sat on the rather dirty floor of the stage to play it.

Although that was the one and only time we ever played that song, it was reported worldwide in the music media. For a long time afterwards, we were getting requests to play it. There’s a video still available on YouTube of Eric singing a few bars of the song from that night. It sounds awful.

We played early in what was to be an all-night event. I left after our spot, so I didn’t see any of the violence that reportedly took place.

Some local toughs showed up looking for trouble and to beat up on some hippies. This led to the Melody Maker, a leading Brit music paper, suggesting the event should have been called “Boot In” rather than Love in.

I left the venue in my VW Beetle (Bug), along with Andy Summers who, one year later, would replace me in The Animals and would later go on to success with The Police.

We headed back to my Shepherd’s Bush flat for a late night cuppa. As we turned into the alley leading to my back entrance to my place, we were accosted by two “rozzers”, cops, in other words.

They wanted to know what we were doing and I explained that we were returning from a gig. They then asked me what I was carrying. I told them it was a bag of laundry, which was true. What I didn’t tell them was that in a pocket of one of the shirts in that bag was a whole bunch of LSD that I had recently scored.

After that, they were very friendly and polite. So much so, that I considered inviting them in for a cup of tea. Fortunately, good sense prevailed, and I didn’t.

On August 8th, we played the Marquee Club in London’s Soho district, a club I had played many times before with Brian Auger. There was nothing remarkable about the gig.

On August 8th, we played the Marquee Club in London’s Soho district, a club I had played many times before with Brian Auger. There was nothing remarkable about the gig.

What was remarkable was that in 1989, someone in Italy released a CD of our performance. It was indeed a bootleg. Some person or persons unknown had stood in the crowd with a cassette recorder and recorded the whole show.

I bought the CD. The sound quality was, of course, execrable. The quality of the music was exciting. If I ever had any doubts about how the band sounded live, this recording would dispel them.

Meanwhile, back in the US, MGM were releasing San Franciscan Nights which would go to #9 on the US charts.

This was a magical time and many magical things happened during that summer. I’ll be sharing some of those magical events over the next few days.